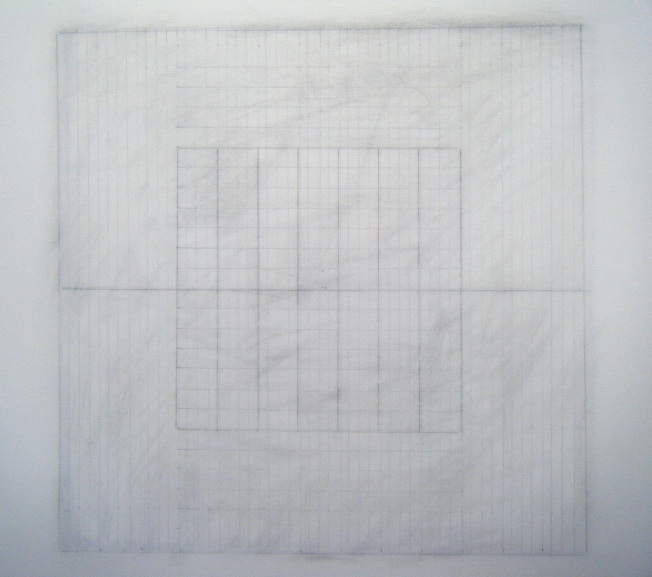

Robert Ryman, Catalyst lll 1985

An exhibition showing a wide range of Robert Ryman’s paintings occupies two large gallery spaces at Dia:Chelsea in New York. My visit to look at his beautiful work was on a grey and freezing wintery day in February. Vittorio Colaizzi quotes Ryman in an essay that introduces a collection of critical writings concerning his art, Ryman: ‘Painters paint in all kinds of ways, but I think that all painting is about enlightenment and delight and wonder’. (Originally published in Robert Ryman, ‘On Painting’, in Christel Sauer and Urs Rasmuller, 1991). In an interview with Ryman in September 2002, the artist who was then approaching his eightieth birthday, described a collector placing one of his paintings in the dark hallway of his home. Deprived of the light and space it needed, Ryman reflected ‘But it’s odd that they seemingly like the painting but yet they don’t understand what it is. Or how it works.’ (Robert Ryman, Critical texts since 1967, ed. Vittorio Colaizzi and Karsten Schubert, Ridinghouse, 2009: 20).

His paintings intrigue me in that on the one hand when faced with walls of mostly white paintings I experience quietude, but when drawing close I am fascinated by the marks and surfaces and his seemingly endless capacity for experimentation. In the Dia show I was particularly drawn to one work, so much so that after leaving the gallery I went back after a while to look again. This work seemed to me to be perfect in its simplicity and slight detail. After an earlier showing of Catalyst III (1985), Ryman spoke of this work, which is an aluminium support held to the wall by four bolts:

‘It’s one of my favourite drawings, that was shown at the Modern, in Bernice’s show (MOMA, New York). It’s not very large 23 x 23 inches, but it’s probably my favourite drawing. It’s just one of these things that is so amazingly simple, but it’s very complex and everything works…What you’re not seeing in the photograph is this line [the aluminium edge of the drawing]. It’s just the line of the metal, but it’s there and it’s important’.